Hotel Domus Belgium

La Chambre, 1972, video still. Courtesy of the artist" alt="Chantal Akerman, La Chambre, 1972, video still. Courtesy of the artist"/>

La Chambre, 1972, video still. Courtesy of the artist" alt="Chantal Akerman, La Chambre, 1972, video still. Courtesy of the artist"/>

Chantal Akerman, La Chambre, 1972, video still. Courtesy of the artist

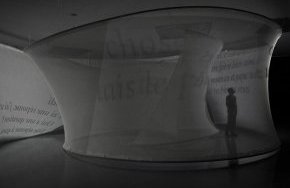

Although the show also expands on a selection of her earlier work, the focal point at the centre of the exhibition is D'est: au bord de la fiction (1993) — Akerman's first installation and a turning point in her career which led to the later emphasis on installation.

D'est was the first installation that brought her work into the gallery and other art spaces. She divides the film into shorter extracts and formally brings the parts together by means of colour, for example, or though movements of the camera or characters within an installation of 8 groups of triptych monitors.

From this work on, we see Akerman start to reach beyond the limits of her movie and start to explore spatial features within the gallery space. Where Akerman's early movies gave her a great deal of control over how the viewer experiences the passing of time within the piece, this power is more limited in the installation pieces, since viewers can themselves more easily 'edit' how long they spend in front of the installation.

Although the show also expands on a selection of her earlier work, the focal point at the centre of the exhibition is D'est: au bord de la fiction (1993) — Akerman's first installation and a turning point in her career which led to the later emphasis on installationChantal Akerman, D'Est, 1993

This documentary is a starting point for another film on show at MuKHA: L'autre côté (3ème partie: Une voix dans le désert), a film made in 2002. The film shows a screen situated in the middle of the desert, set between mountains rising up on either side of the border between Mexico and the United States. Images shot at night of people trying to cross the border alternate on the screen with images of a bustling Los Angeles. When night becomes day, the projected images become invisible. Akerman switches between English and Spanish as she recounts the stories of migration.

Akerman switches between English and Spanish as she recounts the stories of migration.

Other works on view illustrate the course of Akerman's evolution. In her first movie Saute ma ville (1968), a young woman returns home to her tiny kitchen and literally locks herself away by taping the door shut, before starting to do the housework in a burlesque fashion, work that sees her cooking spaghetti, cleaning and doing the washing up in an exaggerated, overplayed way, and literally smashing everything on the ground. As in many of her later films, she questions feminine roles and domesticity.

Chantal Akerman, De l’autre côté (3ème partie Une voix dans la desert), 2002

There is a lot of activity in her first film and the camera follows the subject in a way not typical of her later films, which are slower paced and involve a delaying or suspension of action that has the viewer expecting or anticipating events that feel like they might be on the point of taking place. In La chambre (1972), for example, she starts to make use of tracking shots: a long and slow panoramic shot revolves several times around the room and each time the camera passes, we see Chantal Akerman lying in a different position in bed.

The scanning of architecture and space becomes even more visible in Hotel Monterey (1972), where Akerman films from hallway to rooftop, in the elevator, and in the corridors, using fixed shots alternated with travelling shots. She sometimes focuses on people, but most of the time on empty corridors. There is no soundtrack.

Chantal Akerman, Hotel Monterey, 1972, video still

We get a good insight into her work in Chantal Akerman par Chantal Akerman (1997), which forms part of the French television series entitled Cinéma, de notre temps [Cinema, of our time]. She reads aloud a letter about the making of her self-portrait, addressing what she thinks about the programme and about her work in general. A selection of "rushes" from the film is also included.

We get a good insight into her work in Chantal Akerman par Chantal Akerman (1997), which forms part of the French television series entitled Cinéma, de notre temps [Cinema, of our time]. She reads aloud a letter about the making of her self-portrait, addressing what she thinks about the programme and about her work in general. A selection of "rushes" from the film is also included.

Akerman's work is both directorial and observational. The viewer often becomes part of the film installation; it's as if we are 'really there' because of the sense of inertia that some of the images impart. Some of her later films achieve the suppression of narrative with the absence of a beginning or an end.

In Tombée de nuit sur Shanghai (2009), we see static shots of a river, of ships, and the skyline of Shanghai. At first the scene shimmers (the ships have screens bearing screens bearing advertising signs), and then as it becomes dark, the skyscrapers themselves become screens showing animals, flowers and all sorts of images; the architecture disappears to make way for the advertising, or the architecture in turn becomes the screen. Random noises from the hotel and restaurant compose the soundtrack. There is often a comical notion present in Akerman's work and here she places two tanks of fake fish in front of the projection.